By JOSEPH EBERT

In his seminal essay, Avant-garde and Kitsch, Clement Greenberg positions art in the realm of certain ambiguity. Ambiguity is made up of two separate entities, which act in opposition to each other, placing definite ideas within a haze of frustration. As the title posits, the conflicting entities are the avant-garde and kitsch. What Greenburg concisely and eloquently elicits is the relationship two dissimilar factions have with culture, society, politics, and economics. Yet, what is slow to surface—aside from the realities of financial dependence—is any notion of a coming together between the avant-garde and kitsch. Marx famously solicited that history repeats itself, “First as tragedy, and then as farce.” In this it can be inferred that a duality is present within the evolution of history. What seems ambiguous in both Greenberg and Marx is the Hegelian dialectic. How does what is present work relationally to produce a neo-avant-garde, or an ideology, which illustrates a living culture rather than a culture that merely repeats?

In Greenberg’s analysis the avant-garde is consumed by a fragile elite, which through traditional standards assumes the duty of dictating and translating high culture. Kitsch on the other hand, is familiar to direct assimilation of cultural vernacular; it takes as its basis, the understanding of the uncultivated, sympathizing with familiarity, and synthesizing it as an associative story. How can the avant-garde, associated with an elite minority, exist in society with the majority, the uncultivated, with kitsch? Greenberg uses as his main example a hypothetical “freedom of choice.” This hypothetical is scripted by the analysis of two paintings, Picasso’s Woman with a Fan and Repin’s Cossacks. Greenberg makes the polemic clear: the peasant will choose the Repin painting. The reason for this is because the Repin represents kitsch, and by extension all of the loaded vernacular values inherent to the concepts of kitsch. The peasant displaces actual painterly technique with the Repin because it’s realistic. The image of war in the Repin is also easy; the peasant doesn’t want to come home from a strenuous day at work and think about the meaning associated with the painting, which is necessary for the Picasso. He or she merely wants to sit and be entertained by something that has visually accessible values inscribed to it.

The elitist, or cultivated spectator, will derive the same values from the Picasso that the peasant assigned to the Repin, but these values will come at a “second remove.” The phenomenological and sympathetic values the cultivated has for the Picasso are initially externally driven, and must filter through a set of higher, reflective cultural values, eventually terminating in a better understanding of the values and principles which Picasso assigned to the painting, and inevitably a better understanding of the painting as part of a living culture.

The current state of architecture is one of seemingly indefinite ideology. Ideas and concepts are thrown around in ways that give architecture an infinite ambiguity. It’s as if there’s too much to hold on to, and what is within reach is always moving. Architecture’s identity is something of a haze right now, saturated with philosophies, theories, artistic idiosyncrasies, politics, technological measurability, etc. Our discipline is in a period of farce, with inklings of lingering tragedy. The presence of tragedy within this farcical period is made evident by works of architecture that still try, in revolutionary and progressive ways, to move beyond the sympathetic norms of traditional ideologies.

Contemporary culture is one of indefinite “absoluteness,” struggling to define itself through concrete form. It’s a culture made up of two systems—the avant-garde and kitsch. These two systems make vague any progressive momentum because they are either an “imitation of imitating” or they are trying to make cool intelligent. The values inherent to each system are relative to conceptions of familiarity and unfamiliarity. The values, to maintain a living culture, are “vividly recognizable, […] miraculous, and […] sympathetic.”

Northrop Frye was correct in saying, and Greenberg hones it as well, everything that we are taught, or learn, comes through a filtration system of criticism. Criticism is inherent in the momentum of progress, and effects thusly through the understanding of what has been. The study of history is fictive in a sense. That which is being discussed is born of actual events, but the remembering and recording of said events always filter through a set of subconscious criticisms, whether pedagogical or ideological. Thus, architecture is consistently lent a position, a position which it maintained before the Industrial Revolution and modern Capitalism began to manipulate into production social homogenization, a monoculture.

The current act of taking up arms against homogenization is feeble. Some can attribute such a gaunt state of disciplinary intellect to the lagging economy, but I say that a poor economy presents a greater opportunity to experiment, research, and play. The recession of the Nineties produced a period in which architects could only experiment, research, and play. Zaha did the researching, while FAT did the playing—somewhere they methodologically met halfway through experimentation, leading eventually to application.

Architecture used to mean something; it used to represent the world, the universe; the pyramids of Giza, the Parthenon, these used to represent the universe on earth. They were architectural monuments that spoke of a more ideal paragon for which each epoch would be represented by those who followed. Now architecture is something completely reducible to its parts, something static, something concrete. What we need now is architecture that truly resides in space and time, something irreducible and relative to traditional ideologies. We need an architecture that both cares and doesn’t care about society because it is society.

The avant-garde is the tragic; kitsch is farcic.

Tragedy in architecture is defined as architecture, which seeks, through profound engagement with sympathies and emotions, to overcome the obstacles of the society that it is trying to constructively change. Contemporary architects familiar to this practice are characters like Steven Holl, Thom Mayne, and Zaha Hadid, to name a few. Farce in architecture is defined as architecture, which entertains humorously through methods of criticism and ridicule the hyperbole of society’s customs and institutions. The architecture of farce draws out the norms of society and exaggerates them to the point of absurdity, thus hoping to invoke expedient accessibility, measurability, and sympathy. Contemporary firms familiar to this practice are FAT and BIG.

Yet, what is currently apparent in architecture as a cultural discourse—I remind you that it is a living culture which we seek out—is the need for architects to not only define themselves but for society to define and be defined by architects. Thus, a third entity must be found. The synthesis in this dialectic must be quickly drawn out or contemporary architecture, as an effect of globalization and capitalism, will falter under incestuous homogenization. The discipline will be forced into a consummation of sympathetic brotherly love for the commoditization that is architecture. The avant-garde will rue the day they enter into a compulsory relationship with an architecture of pejorative wit, and visa-versa. The synthesis, in the case of looking at architecture according to Marx’s metaphor, is the Tragifarcic.

The Tragifarcic is not only the dynamic and fluid coming together of the tragic and farcic in architecture, but also the coming together of architecture as a cultural discipline with other disciplines. Architecture as a profession must maintain an elitist stance, but it must also accept the constructive sensualities present in other disciplines like film, art, biology, sociology, psychology, etc. One such practitioner is Jason Payne.

Jason Payne is constitutive of a contemporary polemic about architecture’s presence in a homogenized society, through which technological expediency defines the “freedom of choice” by which the viewer, or societal constituent, reads architecture contextually and phenomenologically. Phenomenological architecture as discussed by Jeffrey Kipnis in his introduction to the book on Steven Holl’s Nelson Atkins addition, is architecture as a “knot of blended perceptions that communicate simultaneously through sensation, intuition, and comprehension to produce a place in the world.” The phenomenological becomes a chronology of architectural effects and the experiences therein associated, accumulating the parts to produce a whole. The whole is singular, and conceived of so within the world. The phenomenological is about storytelling. Payne is attuned to phenomenology, creating worlds of distinct sensation and perception, but he does so through ideological twists of subtly, relating to the relativity of space-time in architecture. Payne, the tragifarcic, has produced two major works for discussion: the first is his PS1 MoMA entry entitled “Purple Haze” and the second is a recently modified structure in Utah entitled Raspberry Fields.

Before a proper understanding of the tragifarcic—my proposal for the next tradition of contemporary architecture—is laid out, there must be a dialogue afforded to the two entities whose hopeful consummation incites the possibility of producing the tragifarcic in the discipline of architecture.

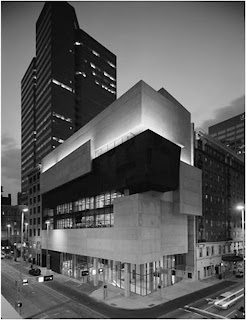

As stated earlier, Zaha Hadid represents the tragic, as can be seen through the Rosenthal Center for Contemporary Art (CAC) in downtown Cincinnati. The farcic example is “The Villa”, a community-civic center outside Rotterdam by FAT.

I grew up in Cincinnati, and it is my opinion that CAC is a great contemporary building, as well as a symptomatic example of tragedy in contemporary architecture. It’s sensuous, warm, silent, irruptive, unexpected. The late Herbert Muschamp was correct in eliciting his “burst of hyperbole” that “the Rosenthal Center is the most important American building to be completed since the end of the Cold War.” He goes on further to say that by meshing together urban and phenomenological aspects present in a globalized society, Hadid was able to define the context of architecture in a contemporary urbanism at CAC.

Penetrating through the brilliance of design, CAC is espoused as tragedy because Hadid accepts traditional notions of nomadism—inherent to a Middle East that she has never looked back to—and twists them to conform to avant-garde conceptions about contemporary urbanism. Tragic, because contemporary urbanism in Cincinnati is a pathetic one. The cultivated spectator is truly a minority here; any possibility of sustaining a reciprocal dialogue between building and visitor is limited, and thus the nature, which maintained the avant-garde, is lost. In regards to the tragic, it’s ironic, because the urban carpet, which pulls up, acting as the “vertical street”, is actually separating a Section-8 housing building a foot to the north.

The “vertical museum”, as it has been conceptually coined, is formulated on the notion of a typical urban building rotated ninety degrees to the vertical. The urban carpet, a continuation of the public street, formalizes the ground plane and the back wall as a continuous surface. This is a reverie on the frail single-surface project; the quarter-pipe defines a possibility of purpose for which a single surface can act as both urban appendage, an extension into a hierarchically saturated public space, or the beginning of the tragifarcic, wherein another discipline, in this case skateboarding, could invoke a surface loaded with contemporary urbanism and the concepts of a typological museum. If only the glass weren’t divider, and the CAC administration weren’t keen on adding to the tragedy of eliminating ideologies, then the urban-carpet quarter-pipe could be experienced by skateboarders as well.

Entry into the museum is from the broad side of the south façade. The idea of urban continuation is reiterated with a dashed line of lights, alluding to the dashed lines painted to delineate lanes on roads. This line of lights is roughly perpendicular to the actual axis of entry (slightly north of west), which visually brings the visitor into the space without him or her actually being in the space, just as the skateboarder is enticed into riding the ambiguous urban-carpet quarter-pipe, but ultimately, not allowed. One might think that upon entering, the massive piers and HVAC enclosures represent a dissolution to the transparency of the ground level, but through the orchestration of light penetration, the manipulation of movement from the outside to inside, and the usage of contrasting black and white on solid planes, the heaviness inherent in such a poched structure evaporates. Yet, unbeknownst to the visitor, the weightless quality of the ground level continues. The dynamic juxtaposition of gallery spaces above doesn’t harness a perception of heavy objects flimsily hovering above. The phenomenological aspects of the building are defined in the possibility of the visitor to read the space “with their feet as well as their eyes”, making greater a “mind-body connect[ive]” experience.

Movement through to the galleries is facilitated by either the mass transit mode of the elevator, which makes the conception of spaces rather static and less fluid, or by taking a zigzagged step-ramp, which runs along the vertical urban-carpet. It’s at this point that the gallery volumes become constituents in a formalized urban fabric. They sit adjacent to and above the urban-carpet, which is now a vertical street. Everything is rotated into the vertical. Still, movement from gallery to gallery is not corrupted by this change of orientation; it is only upon taking the step-ramp that one is thrown into a Piranesian flux of ambiguous space, scale, and light. The zigzagged step-ramp lends to a greater experience of this Raumplan museum. The increasing amount of natural light that saturates these series of steps is like ascending into a glowing-white metaphysics. One gets lost in the variety of gallery spaces.

In 1990 Robert Mapplethorpe was prosecuted by the city of Cincinnati for images of nude men—considered by the city as pornographic—that were part of his exhibition entitled “The Perfect Moment.” CAC is tragic. It’s tragic because in 1990 art left Cincinnati, and so did cultural progress. Zaha created a deeply serious architecture, an architecture that tries to undertake a contemporary urbanism in which art cannot exist.

Cited as the “new generation of postmodernism”, the work that FAT produces in general is rather eclectic and shed-like, a reverie on postmodern canons like Robert Venturi and SITE Architects of the Seventies and Eighties. The oeuvre of their work and the Villa represent within the tragifarcic dialogue the farcic.

The Villa is a community building situated in Heerlijkheid Park in the town of Hoogvliet. Meant to reflect both the industrial past of the local area and the “bucolic ideas on which the design of the New Town was originally based”, this multi-use hall with offices and a café represents a dialogue of postmodern technique and ideologies in a contemporary suburban area. It seems ironic that the history of the town was an industrial one, especially when the original ideas about the town’s design hovered around notions of a pastoral Arcadia, an idyllic rural life. FAT picks up on this contradiction and sculpts a “21st-Century civic architecture” saturated with referential signage and panache.

Immediately the building seems rather plastic in its sheen and appliqué. In a humorously flamboyant manner, FAT uses decorated shed-like techniques to blur the conversation between the industrial past and the originary bucolic ideas. This blurring is achieved through graphic appliqué via a postmodern billboard. The billboard, however, is not merely a flat plane upon which graphic wallpaper is applied, but a sculptural system of three-dimensional layering. The billboard doesn’t make apparent the presence of any floor demarcation in number or height. What the billboard is hiding is a regular box-like interior. At certain moments, moments when the office windows on the rear façade are visible, the billboard becomes more transparent in demarcating the possibility of multiple floors.

The industrial past is portrayed in profile by a timber rain screen cladding system: profiles of industrial towers, silos, gabled warehouse structures, etc. This cladding displays the name of the park, but does so as a deterioration of the billboard. There’s quite a bit of motion and conflict going on between geometries in the graphics of the billboard. The bucolic notions enter into conversation: we see trees and clouds in profile. As the cladding is mere appliqué, it does not need to retain any structural functions. Thus the bucolic tree trunks unnecessarily touch the ground. The canopy of the trees is the timber cladding system wrapper, as well as the form from which the industrial graphics sprout. It’s as if FAT is imposing on the town a conversation of man’s archaic relationship to nature: out of the trees sprouts industry. Here, FAT is drawing on the associations the peasant will make with subconscious notions of primitivism. FAT’s making the architecture easy and kitsch.

Similar connections are instilled with the sculptural appliqué at the entrance. Here the curved and rounded organic shapes suggest a floral quality—nature reiterated. Without the yellow paint applied to these floral profiles, the entrance would become blurred and almost hidden. The Villa is the most prominent man-made structure in the park, and thus its significance is reiterated by its elevation on the site and placement adjacent to a minor canal. Access to the site by park-goers comes by bridge over this canal. The bridge leading to the site from the park is painted an absurd bright pink, and instills another graphic of sculpted text.

The interior is the space that reveals FAT’s absurd humor. The interior structure is painted pink to accent the rigid, normal structure that supports a regular shed-like object. Looking out of the windows reveals the presence of the billboard appliqué. The viewer is made aware that what was articulated on the outside does not transfer through to the inside. The appliqué becomes the frame for which the viewer is suggested to perceive the outside world. The outside world is the park, the visions of Arcadia, visions of idyllic sympathy. The inside world is the sterile, homogenous warehouse, the industry.

It is within this graphic polemic that FAT exists in the farcical world. Although an argument is made about socio-cultural ideologies and histories, the nature of the billboard presents architecture as false. The inherent quality of the billboard is a sort of false word-bubble. This is referential to the sort playing around FAT did during the Nineties, producing mere regurgitation of a postmodern architecture that sat in ambiguity and instability. There was too much farcical theory going on in postmodernism. Even Jenks had to update and revise his diagram of multiplicity and ambiguity thirty years later. How many times can I laugh at a building, or be intrigued by its humor before it becomes meaningless and annoying? How often and how long can the peasant look at the Repin before becoming bored and moving on? Old jokes just seem to lack any flair. The originality is gone. And though we may years later run into it and feel the nostalgic curl of a smile, it will never produce the those first effects which at the time seemed so endearing. FAT. The Villa. They’re just too nostalgic to every hold a position of progress. By relying mere reverie and absurdity, the Villa exists in farce.

In “Kissing Architecture”, Sylvia Lavin coins an architecture that is emphatic to the relationships and results of cross-disciplinary intermingling. The architecture, which she births, is called Superarchitecture. The basic premise of Superarchitecture is elicited by a trope of kissing. Kissing, Lavin defines, is the coming together of two similar surfaces. The initial twoness gets blurred almost to the point of destruction. But the inevitable reality of separation allows the twoness to carry on individually, hoping to share in future possibilities of similar becomings. Kissing aside, what Lavin is calling for is an architecture that gets out of its own way, and does so by interacting directly with the mediums of other disciplines (like music, painting, technology, biology, etc.). Her eloquent rhetoric is however, rather drawn-out and long-winded. The density of ideas and projects solicited, suffocates itself into a heavy generalization, a homogenous critique of the last decade of architecture. She hints at the work of her fellow faculty member Jason Payne, but does so briefly. Like the Middle East for Zaha, Lavin never looked back.

Jason Payne works and teaches out of Los Angeles, a teeming vat of here-and-now architectural thought and production. Yet, he stands amongst a few; a few that understand what the architecture of Greece and Egypt produced, an architecture of cosmological forms, which effected psychological perceptions. Payne understands the homogenized globalized world that is overrun by outlets of technology and speed. Payne assumes the banality that is produced as a norm, but chooses to move beyond. The redundant, heroic claims that architects want change the world is finally applied in the work Payne produces. Through medium-specific manipulation and orchestration, Payne produces an architecture of synaesthetic beauty, the tragifarcic. He really makes the architecture and its effects respond both psychologically and physically, and he does so through time and change.

Formerly a principal of Gnuform Architects, along with Heather Roberge, Payne’s entry into the PS1 MoMA Young Architects Program 2006 competition displays the underlying ideology that resounds in his overall project. Entitled “Purple Haze”, after the 1966 song by Jimi Hendrix, this project uses a layering system of infrastructure to effect vision, hearing, and touch. “Purple haze all in my brain” is translated into the project by the plumbing system which produces both rain and mist. This liquid and gaseous ether represents the “haze” in which the museum-goers, or partiers, become consumed.

Operating under an undulating and perforated canopy, in which layers of infrastructural plumbing are embedded, the partiers’ senses are overwhelmed to a nearly synaesthetic irruption. The canopy, as one continuous unifying system, occupies both gallery spaces and “pinches through the doorway at their interface.” Under the gallery the “unified skin of the crowd” is respondent to the hazed effects the architecture produces. The haze drawls everything to unifying stroll, inducing the partiers to sit down on loungers. These loungers respond to the bodies that occupy and move in them. Their forms contort to create different positions of sitting. The loungers are singular and modular, but respond to the bodies that occupy them and also the other loungers that they come into contact. They too are bodies, and here it’s all about remembering the body.

“Purple Haze” is an outside installation contained within the walls of the museum’s peripheral site. But the project is about interiority more than what the overall form looks like, and what it produces. The sense of sound seems rather secondary. But the interiority amplifies the fuzzy buzz of the city in which the project sits. It wasn’t necessary to add another layer to the canopy to gain access to the fuzzy distortion of Jimi’s guitar; the duo knew a priori the effects any city has on the volumes that occupy it. Payne commits the partier to a synthesis in which the kitsch sounds of downtown New York City mix with the ethereal sensations produced upon the mass of partiers by the hyper-complex architecture of the layered canopy. But the complexity of the infrastructure is never meant to be understood by the partier. The layers won’t unravel to clarify the architectural concept. The partier is the peasant, meant only to experience the hazy ether.

Payne’s concept and design for an abandoned one-room structure speculates on the notions of new authenticities for architecture via modes of cosmetics and notions of cross-disciplinary breeding. Dubbed Raspberry Fields, this former schoolhouse finds itself in the middle of nowhere, responding to nothing of the contemporary culture of the given area. With the strange manipulations Payne applies to the southwest façade, this project truly becomes a place in the world. However, this place in the world is two-faced. The polemic of twoness in the project is facilitated by the interactions originally occurring between architecture and nature. The building is tilted thirty degrees north of west. The southwest façade receives the more dynamic effects of weathering—rain, wind, freeze, and thaw—while the northeast façade remains effected by calmer conditions. The northeast façade resembles the state of its original conception. Over time the southwest façade’s horizontal paneling has warped, twisted, and detached from the house.

Payne’s design understands the natural occurrences taking place, and how those occurrences negatively affected the faces of the original building, most specific to the southwest face. In his project he exaggerates the relationship between architecture and nature, and bolsters those changes by disrupting conventional notions of symmetry, orientation and unity. Payne solicits the discussion of superficiality through a lens of cosmetic application.

The lens of cosmetology in Raspberry Fields accentuates the existing relationship between the effects of weathering on the building’s surface and the design of indirect effects relating to the building in the site. The building’s site slopes down from west to east, putting it on unlevel ground. The southwest of the building is elevated above the ground, as if lifting its skirt.

On the northeast side of the site actual raspberry fields grow in curved rows, while the southwest side opens to an expanse of unoccupied field. The project, however, responds to an indexical diagram of variant densities of striation in the fields flanking the longitudinal axis of the building. The striation and density of the southwest field curves dramatically as it approaches the building. This curved approach implies syncopation with an unknown force, which causes the project to pinch and turn at the coming together of the entry portico and the main of the building.

There is unique quality to the approach. Payne entices the approaching viewer into a flux of reflectivity. If approached from the northeast one would normally not be too attracted by the mundane, unaffected façade, but the placement of rows of polychromatic raspberries acts as a great zone of drawl. Even if the structure is mundane, at least the viewer is placed within a raspberry field of polychromatic sensation. The approach from the southwest would thus be the approach of greatest intrigue, due to the beauty that the weather-warped shingles present. The ground is less intriguing; there are no raspberries here to satiate the viewer’s journey to the exterior of interest. Here, the building is perceived by the peasant as easy and magnetic, and completely sensuous.

The polarity becomes subdued upon entry into the structure. The viewer gets a short and contained view of a storage area. But moving through the space, one gets torqued around into the main space of the structure. All that excitement and anticipation that the exterior elicited seems to fade away. The space is rather banal. The story seems to end here.

So, in some regards Payne induces a sort of “vivid” experience not only for the viewer (elite and lay) but for the architecture and its environment as well. In this case the interior personality/functionality doesn’t seem to take much weight; it’s hard to justify any functional interest in the interior. Here, at Raspberry Fields, it’s all about looks.

The manipulations imposed on the project helps the viewer understand the simplicity in the form of the existing structure, and the intimate experience that takes place between architecture and the real world. Payne tweaks the simple form ever so slightly to help accentuate the zone of greatest fatigue and intrigue. The southwest side gets torqued and pinched to facilitate a moment in which architectural materialism and natural phenomena come together in a “kiss.”

The ability for this project to blossom is immensely fascinating and anticipatory. And when the structure does take full bloom it will reign in the flickers of deep-purples and vibrant oranges, pinks and yellows. This is where the phenomenological of Kipnis takes over; the project is about an application of cosmetics. Counter to the fleeting quality of a kiss in “which time separation is inconceivable yet inevitable”(emphasis added), Raspberry fields will be in winter for years. The fullness of its bloom only present after years of weathering has taken its course. The concept of the project is thus only elicited as a story; the kiss between architecture and nature too vague, too personal, too isolated, to ever really be seen in process. All we see is the architectural end product, the causa finalis, and not the sensual experience that’s been taking place over time.

What’s avant-garde about Raspberry Fields are the methods in which Payne fuses other cross-disciplinary mediums to create synaesthetic beauty. The difference between Raspberry Fields and Purple Haze is that Raspberry Fields stimulates all of the senses, while Purple Haze could only effect vision, hearing, and touch. What’s tragic about Raspberry Fields? Well, sadly, it’s the reliance it has on the farcic.

What’s kitsch about Raspberry Fields is the presence of cosmetology as a new authenticity in architecture; what’s farcic about Raspberry Fields is the absurdity that is drawn out of cosmetic superficiality. That’s the issue with contemporary, neo-pragmatic, practice; it doesn’t care how architecture affects the world, so long as it gives the image of what it wants to sell. Whether it’s a community center in the Netherlands, or a leading Dante research center in Antarctica, farcic architecture is an architecture that never reveals itself to the discipline or the world. It’s merely a humorously pejorative narrative on the presence of a homogenized, low-culture.

We are in a period of farce; a period in which low-humor is the fatigue to architectural intrigue. This is a period in which architects use humor poorly to saturate the representation of their ideologies. The results are schizophrenic, multiplicitous, and quotational, revealing little to no cohesion in articulating a progressive milieu for the discipline and practice of contemporary architecture. The tragifarcic is the kitsch that consoles the peasant’s culture of accessibility and superficiality. The tragifarcic is the avant-garde that moves the mind of the cultivated spectator into new dimensions. Greenberg stated: “The mass must be provided with objects of admiration and wonder; the [cultivated] can dispense with them.” The tragifarcic is a new tradition for architecture that reigns in symptoms of tragedy and farce; the work of Jason Payne marks the beginning of this new tradition. Raspberry Fields instills superficiality to draw the lay into conversation with architecture as a living cultural discourse; the cultivated are enthralled by the architectural speculations found in their second remove. Raspberry Fields is always moving, forever in flux; its mobile dynamism abstracting and corroding the existence of a homogenous globalized world, saturated with histories of Capitalism. What Payne presents is a speculative architecture, a future with a history that rhymes rather than repeats. The tragifarcic.

Works Cited:

1. Greenberg, Clement. Art and Culture; Critical Essays. Boston: Beacon, 1961. Print.

2. Frye, Northrop. "Introduction." Introduction. Anatomy of Criticism; Four Essays. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1957. Print.

3. Hadid, Zaha. "Project Description." Contemporary Arts Center. Web. 29 Apr. 2010. .

4. Lavin, Sylvia. "Kissing Architecture: Super Disciplinarity and Confounding Mediums." Log 17 (2009). Print.

5. Marx, Karl. The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte: with Explanatory Notes. New York, NY: International, 1994. Print.

6. Muschamp, Herbert. Hearts of the City: the Selected Writings of Herbert Muschamp. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009. Print.

7. Payne, Jason. "P.S.1 MoMA Young Architects Competition." Hirsuta Architectural Design and Research. Web. 27 Apr. 2010. .

8. "The Villa." ::Fat::Architecture::. Web. 3 May 2010.